China is proposing to hold a foreign ministerial meeting with the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) next month – a summit that will help expand and strengthen China’s recent “diplomatic attack” in Southeast Asia.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of China-ASEAN dialogue relations. If China’s proposed conference goes ahead, it will also mark a period of China’s deeper engagement with Southeast Asia as the US ramps up its efforts to set up a regional alliance to counter the Chinese threat.

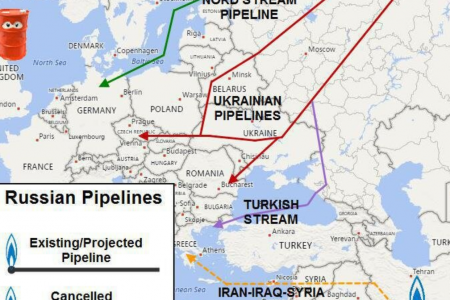

China’s proposal to hold a foreign ministerial meeting next month once again underscores the importance of Southeast Asia to China’s economic and strategic interests. This area has important sea lanes, which is a gateway for China to access global markets, including oil imports from the Middle East, which is extremely important to China. Economically entwined with China, the region’s relatively small states also offer many opportunities for Beijing to increase its influence and undermine what Chinese strategists see as “an inclusive chain” enclosure” designed by the US around mainland China.

Certainly, in any summit, China will focus on portraying China as an indispensable and inevitable partner of Southeast Asia in the fight against COVID-19 and pulling economies of the region out of this pandemic. These “carrots” are likely deployed to “cover-up” China’s recent shows of power in the South China Sea. Since late March, relations between China and the Philippines have been strained when China deployed hundreds of ships around Whitsun Reef in the Truong Sa (Spratlys). On May 12, the Philippines said that through patrols, it had detected nearly 300 Chinese fishing boats and maritime militia vessels that continued to lurk in and around the Philippines’ EEZ, fueling bilateral tensions.

In addition to the diplomatic approach, it is possible that China could also use the summit (which Beijing proposed above) to hold working-level talks to discuss the political crisis in Myanmar. China’s support is widely seen as central to any negotiating process in Myanmar and is likely to build on the “five-point consensus” agreed during the special meeting of the ten-nation bloc on April 24. However, past precedent suggests that China’s approach to the Myanmar crisis will continue to be dominated by the need to ensure stability and protect existing interests and investments Beijing has in this country.

America still “forgets” ASEAN?

Since taking office in January 2021, US President Joe Biden has pushed for a free and open Indo-Pacific strategy – a strategy dating back to the previous administration of Donald Trump – which focuses on focused on strengthening ties with the Quad consisting of the US, Japan, India, and Australia. On March 12, President Biden held an online summit with the leaders of the Quartet for the first time. This is a sign that the group of four nations continues to bond, largely due to shared concerns about China’s belligerent behavior. In addition, in a joint statement over the weekend, foreign ministers of the G7 countries – the group of seven major economies including the US, UK, Germany, Japan, France, Canada, and Italy, expressed “strong opposition to any action” unilaterally escalate tensions and undermine regional stability and the international rules-based order, such as the threat or use of force, large-scale land reclamation, construction of outposts, and such as their use for military purposes. This joint statement did not mention China by name, but everyone understood that the content in this statement was referring to China.

So far, however, the Biden administration has limited access to Southeast Asia and ASEAN, leaving a void in the region and Chinese diplomats have taken the opportunity to “jump in.” Most recently, the foreign ministers of Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines visited Fujian province (China) to hold talks with their Chinese counterparts from March 31 to April 2. The move follows two overseas visits by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in October 2020 and January 2021 to the region. This diplomatic “attack” is also in line with China’s policy of approaching Southeast Asia through “vaccine diplomacy“, under which Chinese-made COVID-19 vaccines have been shipped to most of the Southeast Asian countries.

Which direction will Vietnam go?

ASEAN countries have very different foreign policy priorities. If countries like Indonesia, Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia are said to be trying to “avoid dependence” on China, other countries like Laos, Cambodia, and the Philippines are “depending” on China a lot, especially in terms of economy and supply of vaccines against COVID-19.

A country that is considered to have had very “impressive” activities during the last Chairmanship of ASEAN is Vietnam. Vietnam’s relationship with China has undergone rapid changes in recent times. 2020 is a year marked by many changes in Vietnam-US relations. Vietnam – US relations have become very warm, even though before that, these two countries are two former enemies.

At the same time, the relationship between Vietnam and China seems to show signs of “cooling down.” Although in diplomatic language, the leaders of these two countries always repeat the words “cliché“, the official relationship between the two countries has been almost “frozen” in recent times. From 2020 to the beginning of this year, Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited many ASEAN countries but did not visit Vietnam. Vietnam is also not on the list of countries receiving vaccine aid, even though the Vietnamese Minister of Health has voiced “implicit” for help with vaccines from China.

The biggest factor for the Vietnamese government to be “dissatisfied” with this “16 golden word, 4 good neighbors” is Beijing’s ambition and unruly behavior in the East Sea (South China Sea). Especially after the events of 2014, when China deployed its huge rig into Vietnam’s waters. Vietnamese public opinion boiled with hatred, the Vietnamese government began to see the need to gradually “stay away” from Beijing.

Vietnamese public opinion is indifferent to the recent visit of the Chinese Defense Minister to Vietnam. One question is, why did Chinese Defense Minister Wei Fenghe visit Vietnam and not Foreign Minister Wang Yi? Perhaps China wants to use the visit of the Defense Minister to “remind” the Vietnamese side of the strength of the Chinese military. In 2017, when Vietnam allowed oil and gas exploration in Block 136-03, China threatened to attack the Spratlys, forcing Vietnam to cancel this exploration.

Many people hope that China’s unruly acts, regardless of international law, to monopolize the East Sea will cause Vietnam to change its foreign policy, thereby, moving towards asymptotic with the US and the Quartet.

Dr. Le Hong Hiep, an expert on Vietnam and regional issues at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS-Yusof Ishak) in Singapore, said that the Quartet members are seeing Vietnam as an important security partner, especially in light of the growing strategic rivalry between them and China.

And Derek Grossman, a senior defense analyst at RAND Corporation, commented: “For Vietnam, the existence of the Quartet is desirable.” This is because Vietnam has always wanted to settle disputes with China peacefully and through the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which the Quartet clearly supports.

Although Vietnam has joined New Zealand, South Korea, and some other countries to participate in group meetings within the framework of the “Expanded Quartet” in 2020 to discuss the control of the COVID-19 pandemic, this is a topic not directly related to China.

However, so far, Vietnam has continued to maintain its “4 nos” defense policy. The policy of “3 nos” in the field of defense, including not joining military alliances, not aligning with one country to oppose another, and not allowing foreign countries to set up military bases or use Vietnamese territory. South to fight other countries. Vietnam’s latest Defense White Paper published at the end of 2019 replaced “3 nos” with “4 nos” when adding the principle of not using force or threatening to use force in international relations.

That will probably be the answer to the fact that Vietnam will continue to try to “swing on the rope” rather than expressing a clear position.

Expert Grossman commented that only when the “4 no’s” policy is broken will Vietnam be able to reconsider the relationship between Vietnam and China.

Thoibao.de (Translated)